By Bob Rudis (@hrbrmstr)

Wed 29 October 2014

|

tags:

survey,

datavis,

r,

rstats,

rstat,

-- (permalink)

Gallup released the results of their annual “Crime” poll in their Social Poll series this week and spent much time highlighting the fact that “cyber” was at the top of the list.

(There’s nary a visualization on the Gallup post or in the accompanying PDF, so keep that graphic handy or use the scraped/cleaned poll data and R source code to make your own :-)

It’s a “worry” survey, meaning it’s about personal perception & feelings. In this survey, over 25% of the respondents were victims of cyber crime (hopefully they sample well). As anyone in “cyber” knows, it’s been a pretty rough year (the past few have been as well) and “cyber” has been in the news quite a bit:

so, on the surface, it makes sense that cyber crimes might be on the top of the worry list.

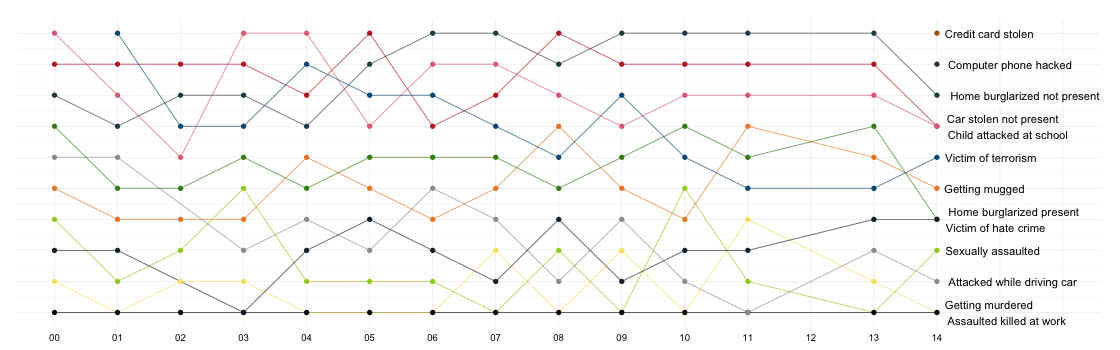

The “crime” survey is given once a year, usually in the fall, and there’s an interesting correlation between this year’s new addition of “cyber” to the question list and what occurred in their 2001 survey when they added “terrorism” to the list. Almost everyone reading this post knows what happed on September 11, 2001 and the revised Gallup poll happend just about a month after the bombings. You can compare 2000-2001 and 2013-2014 survey results in the chart below:

Looking at those year-pairs, we see a similar pattern: the most recent, top-of-mind, in-the-news item becomes the heavy hitter in the poll results, regardless of whether the worry is really substantiatd (though it was “real” to the respondents).

We can coerce these crimes into a “top 10” rank and plot them across time (i.e. a rank-order parallel coordinate chart), though it’s a little tricky to follow the lines in this non-interactive version, so click for larger image:

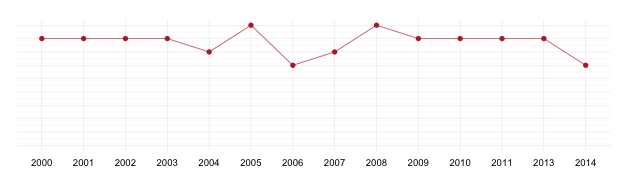

Let’s test the “in the news theory” with “Car stolen not present” crime since it has two peaks:

that we see mirrored in a Google Trends search:

I didn’t poke to see if “home burglaries” were truly greater in 2013 than stolen cars, but the main point is that the “worries” of these survey respondents reflect what makes the news and that doesn’t necessarily mean they need to be your worries, too. It also doesn’t mean that these newsworthy events are likely to impact you. What it may also show is that you may be able to use Google Trends as a proxy for this survey in the future. Sadly, Google Trends doesn’t go back beyond 2004, so it’s difficult to look at the other “spikes” in the top-rankings.

The last point is to always dig deeper if you can get the data. You can find CSV files for the published survey results (it’s not all the data they collected, just what they released) and some R code to make the graphs over on github.

Tweet